A Train Ride to Hudson Bay

By Philipp Budka

I wake up because a bright light is shining directly in my face. For a second, I am not sure where I am. Then I remember: I am in Canada, in the province of Manitoba, on the train from the capital Winnipeg to the small northern town of Churchill at the Hudson Bay. I am in my cabin, in the sleeping car with the window blinds open so I can see the subarctic night sky. The train must have stopped at one of the small places along its way. I look at the clock, it’s 2:30 a.m. I am 40 hours on the train and there are only about eight hours to go.

From Winnipeg to Churchill

My train journey to Churchill began on a Tuesday in February at Winnipeg’s Union Station as part of my first field trip to Canada to explore northern transport infrastructures within the InfraNorth project at the University of Vienna. There are only two Via Rail Canada passenger trains a week from Winnipeg to Churchill and the ride is scheduled for 45 hours. So why not take a car or plane instead?

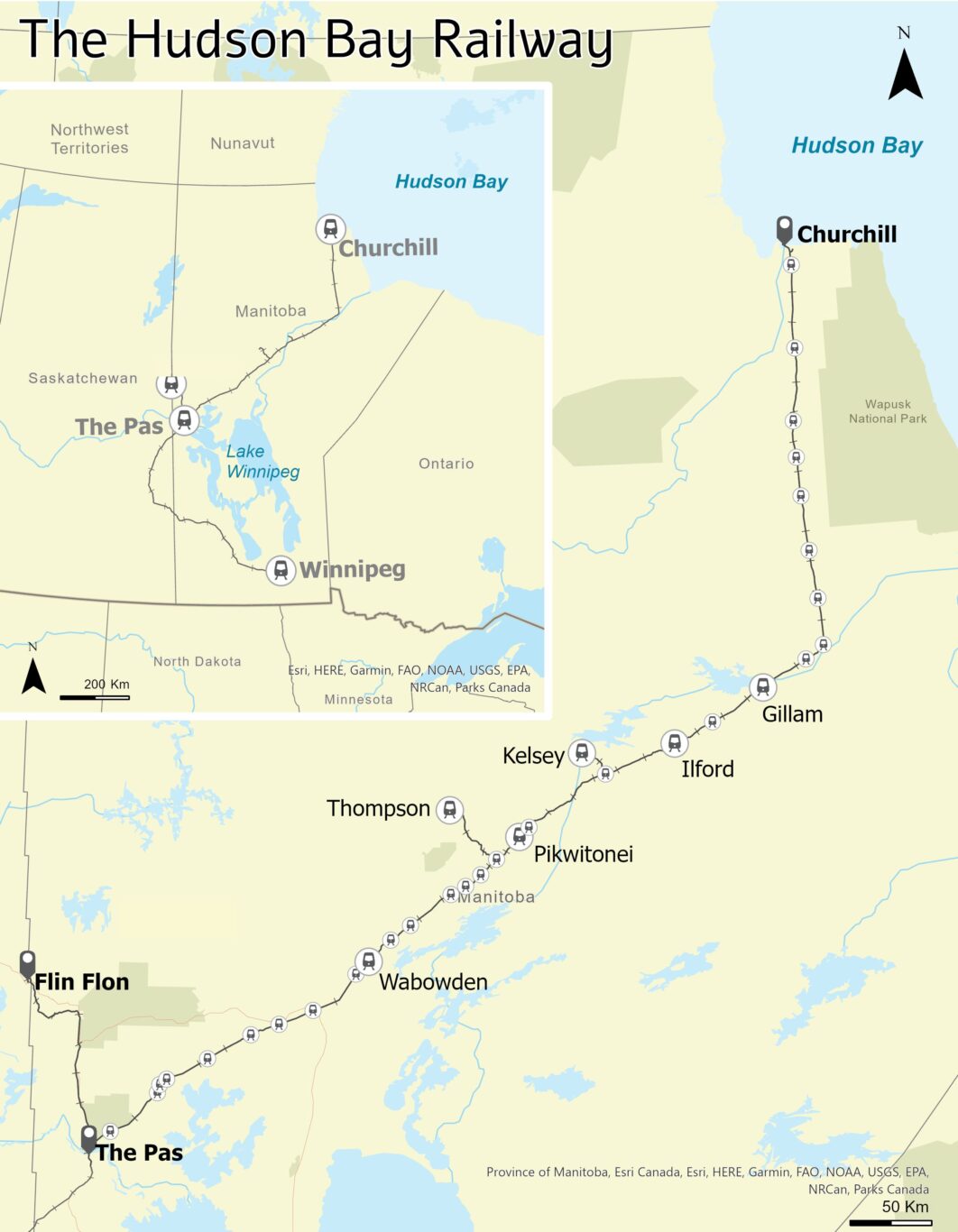

There are no roads between Churchill and other communities. Since 1929, the Hudson Bay Railway has been the only overland connection to Churchill. With the Port of Churchill, Canada’s only arctic deep water port, it was initially built to export Canadian grain.

The town of Churchill developed together with these transport infrastructures. Particularly the railway has become the town’s transportation lifeline. While most of the groceries, tools, vehicles or other bulky goods are shipped to Churchill by train, not all people take the train to get to the town and its 870 residents.

Due to military presence during and after the Second World War, Churchill has quite a big airport that is operated by Transport Canada. And depending on travel and tourist season – Churchill is well-known as the “Polar Bear Capital of the World” – the regional airline Calm Air offers several flights a week between Winnipeg and the town at the Hudson Bay. A plane ticket, however, is about three times the price of a train ticket. Costs of travel would be another reason why people choose the train as means of transportation.

When I arrived at Winnipeg’s Union Station, which was built between 1908 and 1911 according to the plans of the architecture company Warren and Wetmore that also designed Grand Central Station in New York City, a friendly Via Rail employee told me that the train was late. About two hours later than scheduled, I boarded the train with only two other passengers.

The train attendant led me to my cabin in the sleeping car at the very end of the train. The small room looked antique with its turquoise metal furniture, but it was surprisingly well-equipped. The bed, for instance, could be pulled out of the wall and over the toilet. I got fresh water, electricity, a ventilator, air condition, and a heating system; only WiFi was missing.

At the front of the sleeping car, there were a seating area, a quite spacious room with a shower, and public toilets. As I was starting to explore the rest of the train, the attendant told me that due to Via Rail’s COVID-19 regulations I was actually not allowed to leave my car to walk around the train and to meet with other passengers. This, of course, was a big disappointment since I was hoping to talk to other travelers during my journey.

The Prairie

Leaving Winnipeg behind, we rode along the endless fields of grain of Manitoba’s prairie, now all covered with ice and snow. From time to time, the train stopped. One reason for that was to let other trains pass. Via Rail is only leasing railway tracks for passenger transportation.

While the tracks between Winnipeg and The Pas are owned by the private Canadian National Railway Company (CN), the Hudson Bay Railway between The Pas and Churchill (and Flin Flon) was purchased by the public-private consortium Arctic Gateway Group together with the Port of Churchill in 2018. These organizations always give priority to freight transportation. “That’s where the business is”, a train attendant told me during one of those stops.

Another reason for the train to stop was to wait for service crews in automobiles with train wheels that ride in front of the locomotive to check on the tracks and to manually change the track switches of a specific section of the railway line. These crews are usually provided by the line companies and by the local communities that are served by the railway.

Letting passengers on and off the train at one of the railway line’s 54 stops – in most cases on request – is, together with the delivery of mail and packages, usually the main reason to stop. However, because of the small number of passengers during my journey the train didn’t need to stop at many stations, allowing us to make up for at least some of the lost time. Increasing the train’s speed above the average 50km/h didn’t seem to be an option here because weather, soil, and track conditions simply don’t allow that.

The boreal forest

The next morning, it became evident that we were not in the prairies anymore. We were surrounded by boreal forest with its conifers and a few birch trees. Our next stop was the town of The Pas, where the Hudson Bay Railway begins. A new train attendant joined the team and told me that people have generally not been using trains that much recently. This may be related to the COVID-19 crisis, but also because ice roads provide a cheap transportation alternative during the winter months in northern Manitoba.

After stopping at the community of Wabowden to wait for yet another freight train to pass, we arrived at Thompson, with more than 13,000 inhabitants by far the largest town in northern Manitoba, where we should have had a scheduled break of five hours. But since we kept running late for the whole journey, this break was reduced to 20 minutes. At least I was joined by three other passengers in the sleeping car, allowing me to talk a bit more about traveling by train before going to bed in my metal cabin for the last time during this journey.

The tundra

On the second morning the landscape looked different again. The boreal forest had given way to the tundra with its smaller conifer trees and bushes scattered across a plain and icy surface. A constant north wind was blowing from the frozen Hudson Bay. A train attendant told us that it had -40 °C at our final destination Churchill. As the train slowly moved closer and closer to town, I started to realize that this is where I would stay for the next three weeks. This is where I would look into people’s everyday use of transport infrastructures. And this is where I would learn about the importance, the promises, and the failures of these infrastructures. But this is another story.

Please login to post a comment...